The Weird and Jazzy Adventures of Skavoovie & The Epitones

The Batman-loving Boston traditionalists weren’t so traditional after all.

Last September, I released the book Hell of a Hat: The Rise of ’90s Ska and Swing on Penn State University Press. This companion newsletter is dedicated to telling the stories of important bands I wasn’t able to include. The series concludes with Skavoovie & The Epitones, who are gearing up to digitally release their back catalog. An expanded version of their brilliant 1995 debut, Fat Footin’ , arrives on Spotify, Apple Music, and Bandcamp on September 14, with more titles to follow in 2023. Details below.

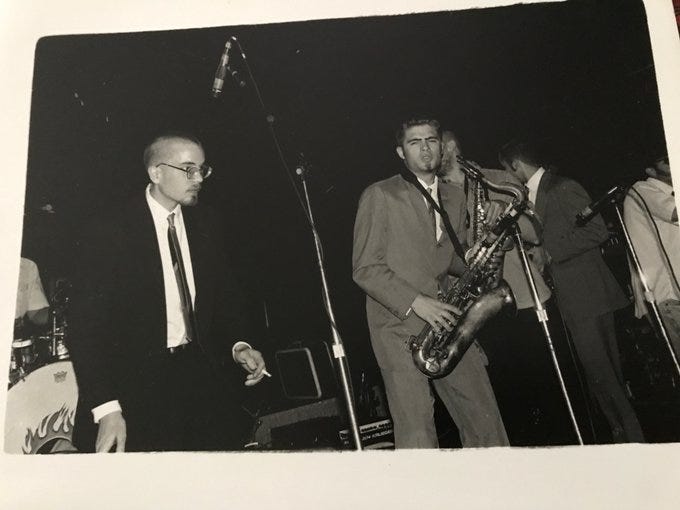

California was a rude awakening—corny ska joke intended and justified—for Skavoovie & The Epitones. It was July 1995, and the hard-swinging, jazz-leaning ska voyagers from suburban Boston were on their inaugural cross-country tour. When their overstuffed Dodge Caravan reached L.A., they played a showcase hosted by Steady Beat Recordings, the label home of hip ’90s bands committed to faithfully recreating the sound of ’60s Jamaica. Skavoovie were not this type of group.

“We were absolutely terrified,” says Skavoovie frontman Ansis Purins, who was 19 at the time. He remembers peering out into the audience and seeing a sea of skinheads. These weren’t the gnarly-looking bruisers with missing teeth that Skavoovie had encountered in Boston. They were impeccably dressed SoCal scenesters in love with a very specific kind of music, and refreshingly, many were people of color.

At the time, the highlight of Skavoovie’s set was their cover of the theme song from 1989’s Batman. There was a part toward the end of the tune where the band would slam the accelerator like the Dark Knight racing to a crime scene, and just before they reached that section, one of the Cali skins shouted, “Don’t speed up!”

There was an unspoken purist rule about maximum beats per minute, and Skavoovie paid a heavy price for breaking it. They sold zero merch that night and consequently had no money to reach their next gig. They had to stay in a scary place they now call “the murder hotel,” and later on, when they hit San Francisco, they had an existential crisis at a 7-Eleven.

“Are we a ska band?” trumpeter Eric Jalbert remembers asking. “Or can we become a band band that plays with other bands that aren’t ska bands?”

That question would become increasingly complicated over the next few years, as Skavoovie & The Epitones rode ska’s third wave to national prominence—then watched their audiences dwindle as the genre fell suddenly out of fashion. By the time they split up in 1999, Skavoovie had engineered a mutant strain of ska-adjacent horn-powered dance music infused with caffeinated jazz and the gleeful kookiness of ’60s cartoons and sci-fi movies. Their final album, 1999’s boundary-pushing The Growler, would’ve had those California skinheads ripping their tiny hairs out.

Regardless of how things turned out, it was never Skavoovie’s intention to disrupt the ska scene. When the group formed at Newton South High School in 1992, Ansis Purins was very much a ska fan. His father, Uldis, had a habit of sitting down each night with a vinyl record and a glass of wine, and the old man’s selections included albums by 2 Tone ska champs The Specials, Madness, and The English Beat.

Purins loved the music and decided to start his own band. After a frustrating experience with some older kids from school who mainly wanted to dick around with Chili Peppers-style funk-rock, Purins linked up with saxophonist Ben Jaffe, trumpeter Jesse Farber, keyboardist Eugene Cho, bassist Rob Jost, drummer Ben Herson, and guitarist Kevin Micka. They later added trumpeter Eric Jalbert, euphonium player Joe Wensink, and saxophonist Jon Natchez, who attended Newton North, the town’s other high school. (Ron Ragona, future co-frontman of Connecticut ska gods Spring Heeled Jack, was very briefly in the lineup.) Natchez was impressed by Ansis’s father’s record collection and menagerie of vintage Godzilla figurines.

“He was instantly the coolest dad I’d ever met,” Natchez says. “I feel like Ansis’s dad informed the aesthetic of the band pretty heavily.” Sure enough, Uldis went on to design all of Skavoovie’s album covers.

From those 2 Tone records the elder Purins played, the group of young friends worked backward and discovered original ’60s ska. They dug the jazzy stylings of bands like The Skatalites and began mixing that music with stuff they liked, like ’60s soul, big-band jazz, and Western swing. They naturally loved L.A. trad kings Jump With Joey, whose sound bridged ’60s ska and the ’40s jump blues that served as its precursor. This eclecticism was notable at a time when most new suburban ska bands were supplementing their offbeat rhythms with heavy punk guitars.

“We’d already realized by seventh grade it was silly to have a mohawk and be dressed like a punk, because it was already done,” Purins says. “That to me was a lot of the spirit: to keep it weird and keep it different and not just be a cookie-cutter ska band. We were a bunch of weirdos.”

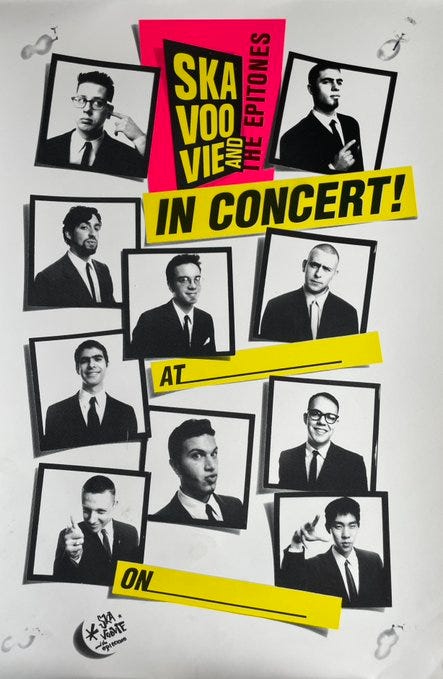

Since there were only a handful of other ska bands in Boston, teenaged Purins and his pals had no trouble landing gigs. Their first show was opening for The Allstonians upstairs at the Middle East in Cambridge, and that meant they had to decide on a name. Up until then, they’d called themselves The Epitones, but Jeremy Mushlin, trumpeter for The Allstonians and later The Slackers, preferred Skavoovie, the Jamaican greeting that—according to one legend—gave ska its name. Mushlin insisted they mash up the two monikers, and thus was born Skavoovie & The Epitones, a tag that would forever bind the group to the ska scene.

Things happened quickly for Skavoovie & The Epitones. They won a battle of the bands at Natchez’s high school and began venturing down to New York City to play shows. Before 1994 was out, they’d recorded the cassette An Evening With Skavoovie and landed the zippy instrumental novelty “Nut Monkey” on Skarmageddon, the seminal two-disc third-wave compilation released by Moon Ska Records. Skavoovie got to know the Moon crew, including label founder and Toasters leader Rob “Bucket” Hingley, and in 1995, they nabbed a deal for their first proper album, Fat Footin’.

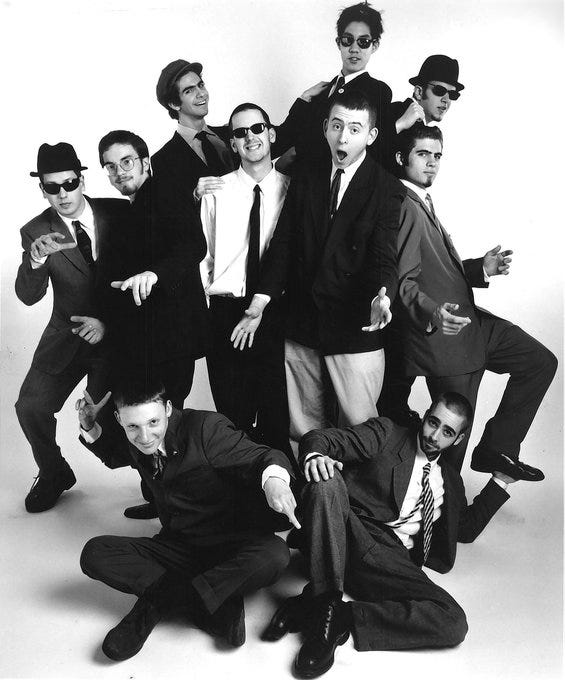

Touted as the “fastest-selling debut in Moon history,” the mostly instrumental Fat Footin’ offered fans a swank, brassy, irreverent brand of ska that wasn’t available anywhere else. Skavoovie were a 10-piece—a rarity even in a scene notorious for large bands—and they really put those five horns to use.

One of the album’s highlights is Skavoovie’s cover of “The Old Man of the Mountain,” the title song from a risqué 1933 Betty Boop cartoon featuring music by jazz icon Cab Calloway. The Skavoovie guys were great fans of vintage animation, and they rented the controversial short from their local library. Bassist Rob Jost used the VHS tape to transcribe Calloway’s complex tune and create a workable arrangement. Because Skavoovie couldn’t quite handle Calloway’s ending, Purins says, Jost came up with a dubby reggae break around the 3:30 mark.

“Rob always was the musical genius,” says Natchez. Indeed, Jost has gone on to become a top-rank session bassist and French horn player whose credits range from Sesame Street and Dear Evan Hansen to Bjork’s 2007 Volta album.

Fat Footin’ also includes the aforementioned “Batman Theme,” composed by Danny Elfman, a man who’d coincidentally played his share of bizarro ska back in his days leading new-wave heroes Oingo Boingo. Skavoovie & The Epitones were inspired not just by Batman—a film the self-professed comic book nerds loved dearly—but also by the New York ska band The Scofflaws, who’d often cover classic movie tunes like Elmer Bernstein’s theme from The Man with the Golden Arm, not to mention Elfman’s dark and circusy theme from Pee-wee’s Big Adventure. “Batman Theme” became Skavoovie’s set closer, and in Jaffe’s estimation, it’s the song that made their career.

Over the next couple of years, Skavoovie’s members gradually finished high school and went off to college. Still, they kept the band going, playing shows on weekends and touring during summer breaks. By 1997, ska had finally burst out of the underground and begun to infiltrate MTV and mainstream radio. Going into their second album, Ripe, Skavoovie & The Epitones sensed opportunity, though they weren’t into chasing trends.

“Ultimately for the best, we were in no way, shape, or form trying to engineer some kind of success,” says Natchez. “We weren’t like, ‘Let’s listen to what’s a hit, and let’s write something like that.’ Which maybe if we've been a little older, we would have tried to do. But we had experienced Skavoovie from within. What it felt like was this steady—and to young minds—inevitable growth from small clubs to bigger clubs: ‘If we just keep doing what we’re doing, people will like us, and we’ll blow up.’”

Released on Moon in May 1997 and produced by Scofflaws bassist Victor Rice, Ripe represented a major vibe shift after Fat Footin’. Instead of big dancy arrangements, Skavoovie embraced their nerdy tendencies and filled a good chunk of the album with elliptical ska-jazz tunes built on gurgling baritone sax, bloopy keyboard textures, and oddball lyrics. It stands as a career high and one of the best things Moon ever put out.

Opener “Japanese Robot” was inspired by the obsession with Japanese robots that Purins shared with his father. “Aquaman” was like “Batman Theme,” except this time, Skavoovie picked a goofier D.C. Comics character and wrote an original theme that, while plenty heroic, acknowledges the absurdity of a man talking to fish. “Aquaman summons a giant sea tortoise!” Purins announces at the end of the track, after most of his bandmates have laid down ferocious solos showcasing their tremendous musical growth.

Purins is the lone credited songwriter on “Frog Spirit,” a moody number seemingly about a ghostly amphibian haunting the lake behind the narrator’s house. In fact, Purins wrote the song about struggling with ADD, a condition he would later be diagnosed with.

“It’s about a kid that wants to be doing his thing and doing things right, but he just can’t focus,” Purins says. “He loves nature and running off instead of doing his chores. This kid goes off to the lake and catches frogs, because he loves doing that. That is what makes him who he is … It’s a pretty out there.”

At no point on Ripe—or anywhere in the Skavoovie catalog—does the band sing about rude boys or ratchets or anything related to Kingston. “We always had a lot of contempt for bands that we thought of as costume party bands,” Natchez says. “You know, like trying to put on outfits and fake Jamaican accents and sing about topics that were on those old ska records but weren’t in any way relevant to their own lives. With Ripe, we really leaned into the stuff we were more into.”

As it turned out, 1997 was the peak of ska’s popularity. That was the year of MTV Skaturday and major radio hits by Sublime, Reel Big Fish, and The Mighty Mighty Bosstones. Unfortunately, Skavoovie’s killer music video for the noirish Ripe gem “Blood Red Sky” never joined clips by Moon alum The Pietasters and Mephiskapheles on MTV’s venerable 120 Minutes. (It did air once—though not in full—on the short-lived series Indie Outing, hosted by Janeane Garofalo.) In the two years that followed, ska’s boom gave way to the unavoidable bust, and by 1999, the once-thriving national scene had crumbled to bits.

“We hated all ska bands at this point,” Purins says, explaining the impetus for Skavoovie to venture even further afield on 1999’s The Growler. The group recorded the album during a yearlong break from college while living together in a house in Brighton, Mass.

“It was this really hard and depressing year,” says Natchez. “Our [concert] attendance was declining. Our money was declining. That was when we started getting into, ‘Oh, we’ve got to write songs that people will like. We’ve got to write a hit or something.’ There was a genuine, organic interest in more conventional pop writing, but there definitely was, for the first time, a more calculated [approach]. ‘We’ve got to figure out how to make a go of this for real.’ And that did not positively impact a lot of the music.”

The Growler arrived on Shanachie, since by this time, Moon Ska had succumbed to cashflow issues brought about by plummeting sales and insider embezzlement, among other things. Had it been released on Moon, it would’ve contended with Mephiskapheles’s 1997 left turn Maximum Perversion as the weirdest CD in the label’s history. The Growler plays like a far-out jazz album that just happens to include offbeat rhythms, and the cartoonish likes of “Tiny Machines,” “Captain Future,” and “Zombie Song” pick up where “Japanese Robot” and “Aquaman” left off.

As an intended pop crossover released in the time of Korn and Limp Bizkit, The Growler missed the mark. As a final statement from a band with “ska” in its name trying to make an innovative quasi-ska album for kids losing interest in ska, it’s a remarkable achievement.

While some fans stuck with Skavoovie all the way through The Growler, the band noticed a lack of loyalty among one-time ska fans fleeing the scene. “The two thousand people who came to the Ogden Theater in Denver [two years earlier] were just there for a ska show—they weren’t there for us or any of the other bands,” Natchez says. “That reflected itself in our album sales, and in the critical response, such as it was. I don’t even think a lot of people wrote about [The Growler].”

What followed was a “slow death” for Skavoovie & The Epitones. They played crummier and crummier tours that earned less and less money, until they finally decided to walk away. Thankfully, nobody had come into the band with unrealistic expectations.

“Very early on, when Moon gave us the record deal, I don’t think any of us thought we were going to be doing this forever,” says Purins. “I got the impression we were extremely lucky to be thinking that way, that this isn’t going to be paying our bills—ever. This was a fun wave. Who else gets a chance to do this when you’re 16 years old? You want to tour the world with your ska band? Of course you say yes.”

Everyone has remained close since Skavoovie split up, and everyone—not just session ace Jost—has found success in their respective fields. Purins is a fantastic illustrator and cartoonist. Cho and Herson played in the righteous neo-disco band Escort, and the latter is an award-winning creative director and producer. Natchez has performed with the likes of Beirut and St. Vincent and David Byrne, and he’s now a member of The War On Drugs, with whom he won a Grammy in 2018 for the album A Deeper Understanding. Latter-day guitarist Daniel Neely became an ethnomusicologist and traveled to Jamaica to write his Ph.D. dissertation on mento music.

In 2011, Skavoovie & The Epitones toyed with the idea of reuniting and recording a new album. More than 15 years after pondering, “Are we a ska band?” in San Francisco, Skavoovie were apparently interested in making a real-deal trad-ska album. Purins and Cho had the whole thing mapped out.

“We were going to listen to a ton of old ska records and identify all the weird tricks and things that we never did, like vocal harmonies and crazy percussion with gourds,” Purins says. “We were going to use those elements and bring that out more, instead of being Herbie Hancock jazzy like The Growler was. To reel it in, in a sense, but in our own way.”

Unfortunately, that project fizzled out due to the logistical challenges that come with coordinating 10 people in different cities around the world. It’s like “wrangling a thousand cats,” according to Purins. But now, a decade later, there is some exciting news on the Skavoovie front. On September 14, 2022, the band will release an expanded edition of Fat Footin’—an album that was previously unavailable digitally—on Spotify, Apple Music, and Bandcamp. The collection will include a cover of the Skatalites chestnut “Beardsman Ska” and an alternate version of Skavoovie’s own “Riverboat.”

A deluxe edition of Ripe—which has also been absent from streaming services—is set for January 2023, followed by a special 7” featuring an unreleased version of “Nut Monkey” backed with the rare cut “9 Dragons.” The rollout will end with a career-spanning compilation of live recordings and rarities later in the year.

It’s unclear whether Skavoovie will ever reform on stage or in the studio. Purins is reluctant to use the word “never,” but given the rich post-ska lives everyone has built, a reunion seems unlikely, if not unnecessary.

“I would want to sound really, really good and bring something new to the table,” says Purins. “But why would you want to revert back to your old band when you’re doing something new and great, and that you love?”

And besides, Skavoovie’s legacy is secure. They remain highly regarded among ska aficionados who don’t take things too seriously or need their music to sound exactly like The Skatalites. Strict historical accuracy was never the point. As Jaffe sees it, Skavoovie and their fellow ’90s ska revivalists were spiritual descendants of the Nuggets-era garage-rock bands of the ’60s.

“It was a bunch of guys that wanted to play blues music but were maybe a little too young to do it,” Jaffe says of those ’60s groups. “We wanted to play this Jamaican jazz, and we were too young. But we had all this energy, and we tried all this crazy shit that maybe they wouldn’t even have tried. So in that way, we were part of the last pre-Internet garage movement.”

For more great stories about ’90s ska, check out my book Hell of a Hat: The Rise of ’90s Ska and Swing, out now Penn State University Press.